Intel’s problem is not as simple as the collapses of other technology companies, as US officials are calling the company’s collapse a security issue.

When news broke in early December that Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger would be stepping down, it sent the tech industry, and chipmakers in particular, into a tailspin. Intel’s statement was the official side of the story, of course, because within hours, Reuters, the New York Times, and Bloomberg were reporting a different story: the company’s board wanted him out.

Three and a half years ago, Gelsinger laid out a four-year plan to revive Intel, which had been mired in a series of problems, but he was forced to leave before the deadline.

It happened so quickly that Intel didn’t even have a strategic successor in mind. It also seemed so certain that Gelsinger would no longer be an advisor to the company.

Intel has been on the decline for years: it missed the smartphone revolution, struggled to control the quality of its chips, lost customers like Apple to other chipmakers, and now risks falling behind on the AI bandwagon.

Intel’s problem isn’t simply the usual ups and downs of other tech companies, with U.S. officials calling the company’s collapse a security issue. Not only is Intel one of the leading makers of computer chips, it’s also one of the last companies to design and manufacture its own chips, rather than outsourcing the latter to Asian companies.

The United States needed Intel’s advantage in particular to reduce its dependence on Taiwan, or, more accurately, to counter the possibility of China taking control of Taiwan. But was Glassinger’s management that hopeless? Or were there bigger issues driving the trend?

Why was Gelsinger’s CEO initially welcomed by employees?

Gelsinger was loyal to Intel, even before he returned to lead the company in 2021. He joined at age 18 and spent 30 years at the company, from 1979 to 2009, fulfilling his potential.

Even some of the people who were laid off later during his tenure believed he was the right person to save Intel. They believed in Gelsinger’s strategy to regain leadership in the chip market, they liked that he was an engineer himself, and they welcomed the fact that he had come to solve long-standing technical problems that previous executives had left behind (or ignored).

Gelsinger was the lead architect of the 486, Intel’s flagship processor in 1989, which launched the company into its biggest growth phase as the first x86 chip with more than a million transistors. He later became Intel’s first chief technology officer, and had a significant impact on the development of industry-standard technologies like USB and Wi-Fi, as well as the design of Intel chips.

Intel was already in a difficult situation before Gelsinger became CEO. The company was regretting its decision to skip the iPhone and was failing to make a mobile chip for Android phones. In short, Intel missed out on the smartphone revolution.

How did Gelsinger plan to turn things around? Perhaps it all came down to making up for a big mistake: when Intel invested in a technology that its competitors later used to overtake it.

What did Gelsinger have in mind for Intel?

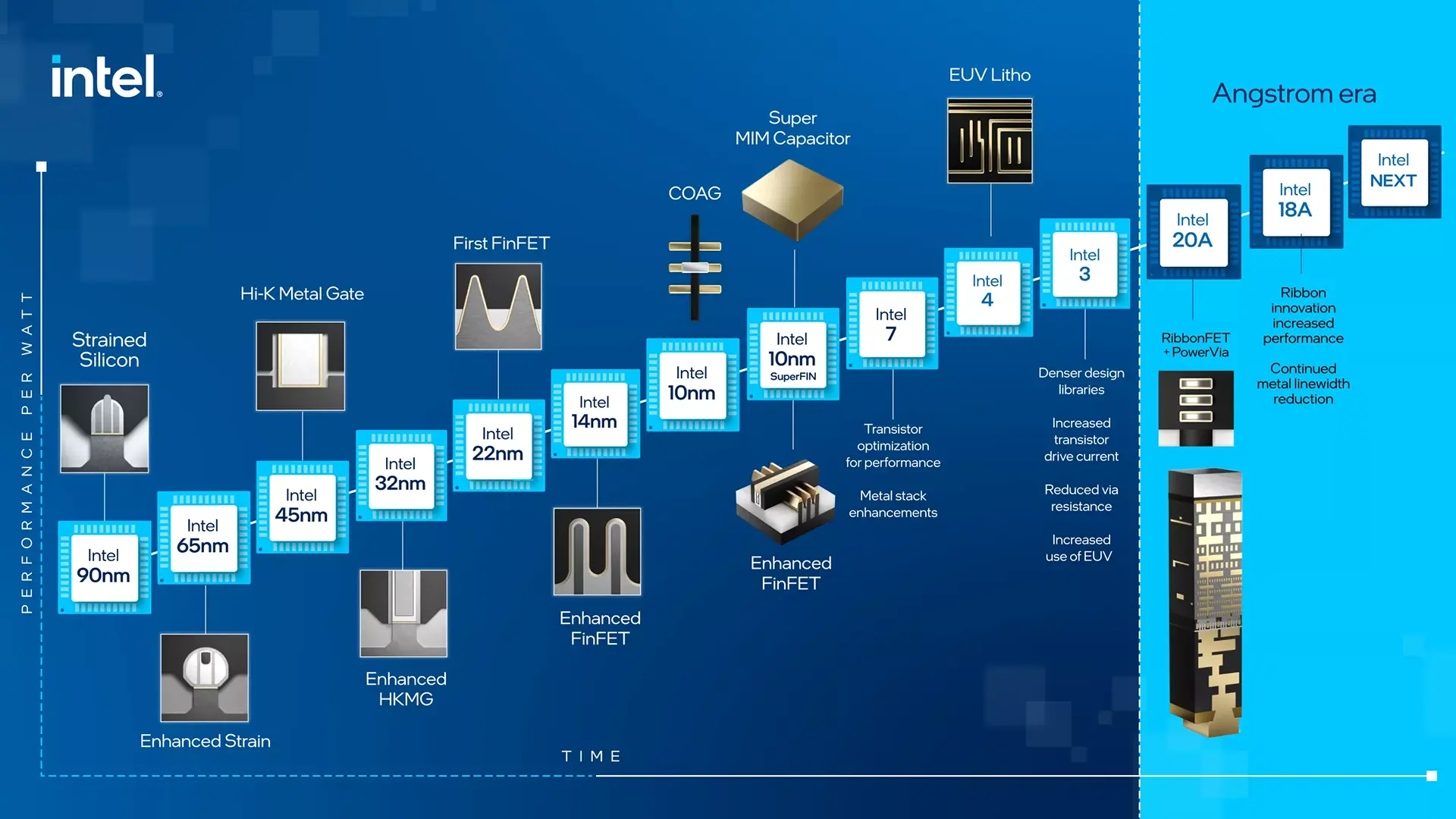

More than a decade ago, Intel invested billions of dollars in the Dutch company ASML, which today is considered one of the most important companies in the chip industry: in fact, ASML is the only company in the world that makes highly complex EUV machines for the production of the most advanced chips.

Intel initially believed in the technology and even bought $4.1 billion in shares, but then decided not to order the expensive machines. In contrast, Taiwanese company TSMC took the risk and became the undisputed leader in the chip manufacturing market, now producing more than 90% of the world’s advanced chips. Samsung, on the other hand, has also joined the ranks of EUV machine customers.

In an interview in 2022, Gelsinger bluntly called Intel’s choice a “fundamental mistake,” saying, “We were counting on this technology failing. How stupid could we be?”

Gelsinger decided to embrace EUV, while simultaneously giving the technology departments a blank check to outpace TSMC.

He also wanted to build the capacity to mass-produce these chips, investing billions of dollars in new factories in the United States and eventually offering his chipmaking services to competitors.

Thus, “five lithography nodes in four years” became Intel’s slogan. In other words, Gelsinger committed his company to delivering five different generations of chips in just four years, each with smaller transistors than the previous one.

Not only did Gelsinger promise to catch up with its powerful competitors, he also guaranteed that Intel would once again lead in silicon technology by 2025, the end of its four-year plan.

Intel’s move came at an incredible cost: tens of billions of dollars in foundry construction, numerous other setbacks along the way, a halving of the company’s stock price, and, of course, unprecedented layoffs.

In August, for example, Intel announced it would lay off 15,000 employees and eliminate all nonessential processes. One of the laid-off employees said:

The level of layoffs over the past two years has destroyed the morale of many employees. Even if you survive a round of layoffs, you don’t know if you’ll still be here in three to six months. This situation causes employees to do the bare minimum, become indifferent to progress, and eventually leave Intel for other companies.

While Intel’s core businesses are still profitable, they are experiencing steady revenue declines. One of the main reasons for this was the high cost of developing Intel Foundry, which was actually financed by cutting the budget of the company’s revenue-generating products.

In this regard, a former employee of the company told the media that Intel’s Meteor Lake and Arrow Lake processors were supposed to have a special Adamantine cache and surpass competitors thanks to this advantage, but the above program was canceled due to costs.

Intel’s board’s gradual distrust of Gelsinger

To make Intel the leader in the chip industry, Glassinger had to focus on changing the concept of leadership: While Nvidia has become the world’s most valuable company thanks to the AI craze and AMD is following Nvidia’s lead, Intel’s Gaudi AI accelerator hasn’t even met Glassinger’s adjusted revenue promise of $500 million per year.

With data center businesses focusing on GPUs rather than CPUs, Intel has not had a strong product in the graphics space.

Although the Lunarlake processors seemed to be completely redesigned to close the gap with the company, Intel eventually revealed that their production was not only uneconomical, but also increased the company’s dependence on TSMC.

There is even a worrying possibility that mass production of 18A chips next year will be far behind TSMC. The New York Times, reporting on Gelsinger’s departure from Intel, writes:

Recently, some Intel customers have learned that the company’s most advanced manufacturing processes, called 18a and 16a, are far behind TSMC. According to one industry official, TSMC currently produces about 30 percent of its 2-nanometer chips without defects, while the rate for 18a chips is less than 10 percent.

“AMD was able to reinvent its design and architecture very quickly, but Intel couldn’t, and it didn’t seem like a priority for them,” said Patrick Moorhead, senior analyst at Moor Insights & Strategy. “How is it possible that the company’s data center business is shrinking while Nvidia is growing so much and AMD is doing so well?”

Ultimately, even though Intel has other AI products in the pipeline and is planning to launch Falcon Shores in 2025, it still seems to have missed the AI train, just as it missed the mobile market years ago.

According to a source familiar with the matter, who spoke to Reuters, the New York Times and Bloomberg, Gelsinger’s forced retirement was the result of a loss of trust from the board:

The Intel board decided that Mr. Gelsinger had to go; Because his expensive and ambitious plans to revive the iconic semiconductor maker weren’t moving fast enough.

Bloomberg also points to other board concerns:

In a recent meeting, the board expressed concern that Intel didn’t have enough competitive, powerful products. They thought the company was working on custom chips instead of focusing on manufacturing that group of products.

Intel and the Fences of the US CHIPS Act

The key part of Glassinger’s plans was an agreement to receive about $8 billion in aid from the US government under the CHIPS Act budget framework, which was passed in 2022.

The deal, finalized on November 26, 2024, made Intel the most prominent example of Joe Biden’s efforts to reduce America’s dependence on Asian technology suppliers, at a time when trade tensions between the US and China are at their peak.

On December 4, 2024, David Zinsner, one of the company’s two interim CEOs, assured investors that Intel’s strategy would remain unchanged.

The CHIPS Act funding for Intel was one of the most significant U.S. moves to reduce dependence on Taiwan.

But some technology experts believe that Gelsinger’s hasty departure could be a prelude to a move that once seemed highly unlikely: Intel’s move to reduce or eliminate direct chip production, a move that would deal a serious blow to U.S. efforts to revive its domestic semiconductor industry.

Intel Chairman Frank Yeri’s comments immediately after Gelsinger’s departure fueled these speculations. He emphasized that the company should focus on product design and development, not the physical production of chips.

Financial analysts also believe that Intel’s exit from chip production would be the best move for shareholders. “On paper, at least, Intel’s product business would be much better off without the factory,” says Ben Bajarin, an analyst at Creative Strategies.

Intel Foundry will likely need to spend tens of billions in the short term to become profitable. In 2023 alone, the business posted an operating loss of $7 billion, and the company’s stock has fallen more than 50% since the start of 2024.

Intel’s CEO has called product design and development the company’s primary focus since Gelsinger left.

The first signs of internal discord emerged in August, when Intel announced it was scaling back its investment plans. In September, the board announced after a packed meeting that it was delaying the construction of two chip factories in Europe and would spin off its manufacturing division into a separate subsidiary.

But separating Intel’s various businesses is not a simple process, just as AMD went through a lengthy process to separate its manufacturing division in 2006.

Intel, on the other hand, has a limited window of opportunity to collaborate with rival TSMC on PC and data center chips, which are likely to be produced in 2026.

The company is due to receive its first check from the US government in the next few weeks. This will make it more difficult for Intel to exit the chip business, as the CHIPS Act has specific provisions for this.

According to the terms of the agreement, which Intel filed with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, the change of ownership of the foundry business requires the buyer to accept Intel’s investment commitments or risk being sued by the Commerce Department for the return of the money.

More government aid to Intel depends on Trump

Intel is the government’s only hope for a domestic chipmaker, as it is the only American company capable of making advanced chips. The current state of the CHIPS Act under President Donald Trump is unclear.

Trump will now have to consider whether the government will do anything to help Intel, and if so, what kind of help it will provide.

Even if the complexities of the CHIPS Act deal are resolved, analysts are unsure who could (or would) buy a manufacturing business with such huge capital needs. “You have to have the financial ability to buy it and you have to know what to do with it,” says Patrick Moorhead of Moor Insights & Strategy. Companies like TSMC and Samsung would have to go through a lot of regulatory scrutiny to do that. Otherwise, buying the unit would require a large investor like SoftBank to handle the high risk.

Some speculate that a Middle Eastern sovereign wealth fund could step in.

Industry experts believe that selling Intel’s manufacturing operations at a time when chip production capacity is largely limited and TSMC has a large market share will present the company with other challenges:

Intel still needs chips for its products such as PC processors and data centers and needs to ensure its chip supply.

ARM CEO talks about Intel’s problems after Gelsinger’s departure

Arm CEO Rene Haas spoke on The Verge podcast about his friend and rival, Gelsinger, retiring. Haas’s comments are especially significant because he had been in talks with Intel to buy a large portion of the company before Gelsinger was ousted.

Haas said in part:

“As someone who has spent my entire career in this industry, I find what happened to be tragic. Intel is an innovation powerhouse. At the same time, in our industry, you have to innovate all the time. There have been many great tech companies that have become just a memory because they haven’t reinvented themselves.

I think Intel’s biggest challenge is that it still doesn’t know whether it should operate as a vertical company (designing and manufacturing chips) or just do the design and outsource the manufacturing (fabless model).

“Pat Glassinger had a very clear strategy and he saw verticality as the path to success. I think when he made this strategy in 2021, he wasn’t thinking about a three-year plan, he was thinking about a five- to 10-year plan. Now that Glassinger is gone and a new CEO is coming in, Intel has to make a decision.

Personally, I think vertical integration is a very powerful model. I think Intel would be in a great position if they could do it right. But the cost of doing it is so high that it’s unlikely to be achieved. It’s like a mountain that’s too big to climb.”

Haas declined to comment on the Intel acquisition, but he went on to say of his earlier discussions with Gelsinger:

“However, when you operate as a vertically integrated company and the strength of your strategy is that you own both the product and the factory, you have a huge potential cost advantage over your competitors.

When Pat was CEO, I told him more than once, ‘Let’s license the logo.’ Because the factories need high volumes, and we could provide that volume. But I couldn’t convince Gelsinger.”

Gelsinger’s hasty exit, even in retirement, was a reflection of deeper, structural problems at Intel. He wanted to reverse the company’s past decline and put Intel back among the industry contenders by mass-producing 18A chips, but the board apparently didn’t like the progress of his four-year vision.

According to some experts, the economics of Intel Foundry are so challenging that it’s impossible to separate it without a massive injection of cash. On the other hand, receiving CHIPS funding would mean that the U.S. Commerce Department would oversee any changes in ownership of the company.

In other words, if Intel owns less than 50.1 percent of the new company or loses its voting rights, the U.S. Commerce Department would have to ensure that the company continues to make good on its promise to manufacture chips domestically. This would certainly make it more difficult to completely separate the foundry.

Intel appears to be at its most critical juncture in its history. Immediately after Gelsinger’s departure, the company’s changes continued with the introduction of two new board members: Eric Morris, former CEO of Dutch company ASML, and Steve Sangy, CEO of Microchip Technology. Will these new developments help investors turn their attention to Intel Foundry, or will the next US administration determine the company’s ultimate fate?